Just when you start to lose track of time, when you lose track of your surroundings, when you begin to recognize, in total immersion with one single object, reality catches up on you. No time for feeling deep in modernity. The guard of the museum will tell you to leave because it is closing time.

The protagonist in Salima Moisseron's short text „About the Rose“ finds themselves going repeatedly to the Whitney Museum for Modern Art to observe Jay DeFeos monumental oil painting „The Rose“. DeFeo had been working on the piece from 1958 to 1966, layering oil with wood and mica on canvas, sculpting it with a knife, waiting for it to dry and start again, tirelessly. It grew and reached a height of eleven feet and a weight of almost a ton.

From the center of the painting, three-dimensional rays spread to the corners of the canvas, making think of light or the sun. The sharp lines crumble towards the edges of the canvas and dissolve into cloud-like shapes, revealing the materiality of which they consist, connecting the piece back to earth and reminding of the physicality of the process of making it. The dissolving rays also signal decay and the time that passed making the artwork and hiding it. While contradicting the inherent perfection of the shape it is telling the story of its burial and resurrection. A human works against and with material for an idea, in obsession, working against and with resistance and against and with time, tediously. Negotiating the ambivalences of existence and using art as a matter to deal with it. She called her work an “idea that had a center to it.” The canvas was as big as the window of the studio in which DeFeo placed the painting and from where she worked on it. It replaced the window and its light. It shed the outside away from the studio. It became one with the wall.

By creating ever more layers of paint she would at the same time reduce the space of movement in her home. The bigger the painting got the smaller her ability to distance herself from it. As though DeFeo wanted nothing more badly than to bury herself in her own paint.

Only when her studio had to be evicted, DeFeo stopped working on the painting. As captured in the Super 8 short „The White Rose“ (1967) by Bruce Connor, the wall had to be removed partly by the movers to free the painting from the building. It became also visible that the studio was covered by the paint, a seemingly moldy patina, covering everything to transform it in a unifying material, a sacred tomb that consists of the same material as what it entails. After it entered the outside world, DeFeo stopped making art for four years. „The Rose“ was first shown at Pasadena Art Museum. It was shown at a time, in which there was no longer space for monumental works that required so much focus and time. It marked the end of a time.

In Moisseron’s text it becomes clear that it wouldn’t be possible to create such an artwork today, or that the protagonist thinks that creating an artwork like the Rose today isn’t possible anymore. „We are now in the modern world, nobody cares about the truth darling. If you want it to make it as an artist today and make a change, you should be a political artist. Do something about social justice, against capitalism or about gender“.

After having been exhibited in the San Francisco Institute in 1969 it was too heavy and large to be moved anywhere else. Financially DeFeo also wasn’t able to get it out of the Museum, store it in her home or store it somewhere else. It was then stored behind a wall of a conference room. Only a few centimeters of the painting could still be seen on top. People forgot about the piece, a perfect melt between sculpture and painting, that after being buried turned into a mere rumor, before it was excavated and restored again in 1995. With time, the painting had different names. Initially, DeFeo named her piece „Deathrose“ not knowing of its eventual fate, and of her own death preceding its resurrection. The painting is now exhibited in the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York.

The same energy, the same movement that was needed to carve the oil into the sun-like shape, was needed to dug it up behind the wall, the same movements had to be made to restore it, reminding us of the past and the shift in art and time.

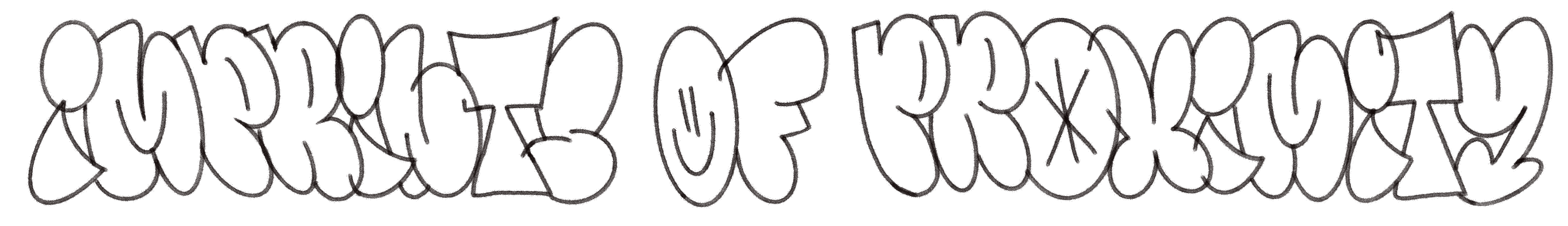

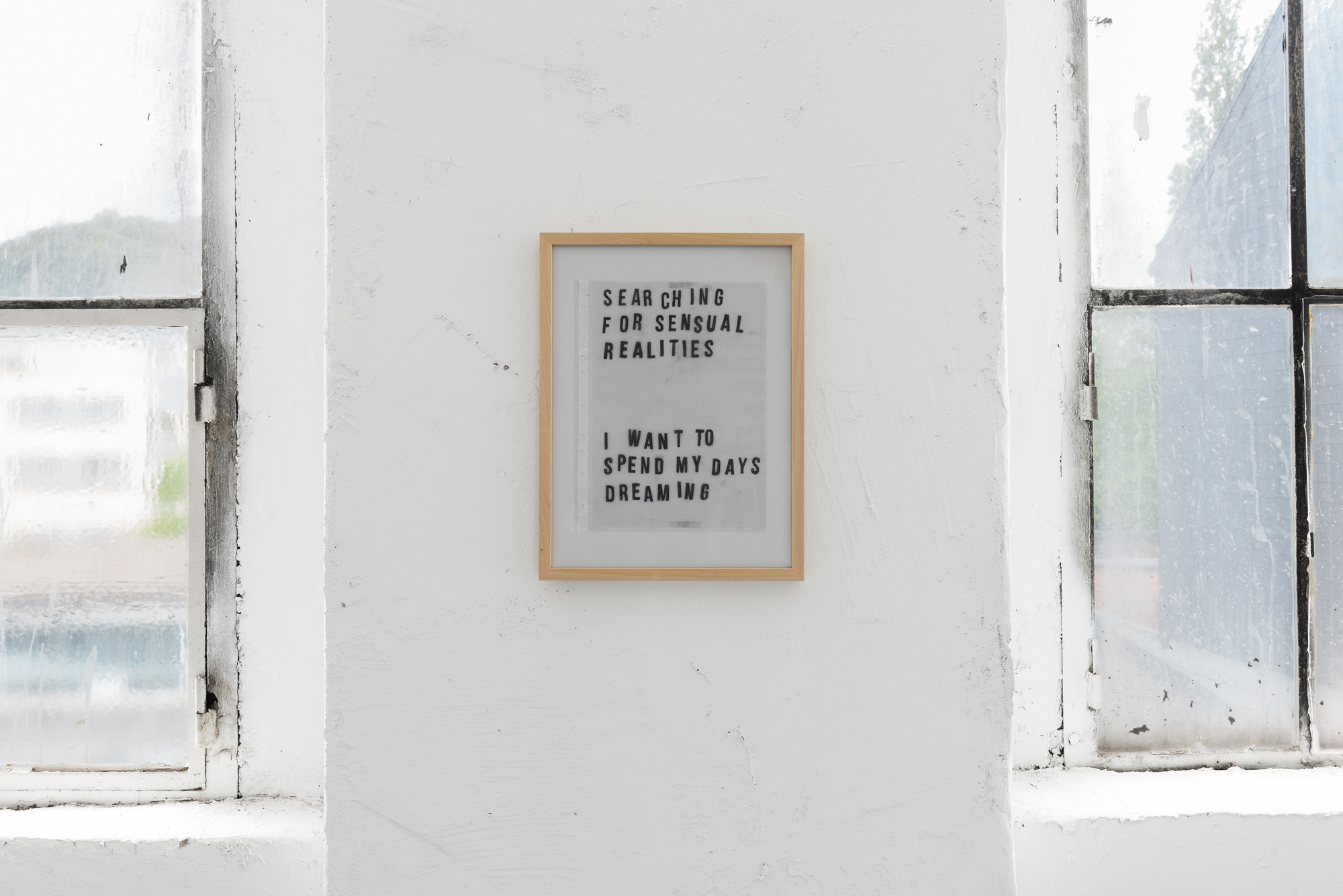

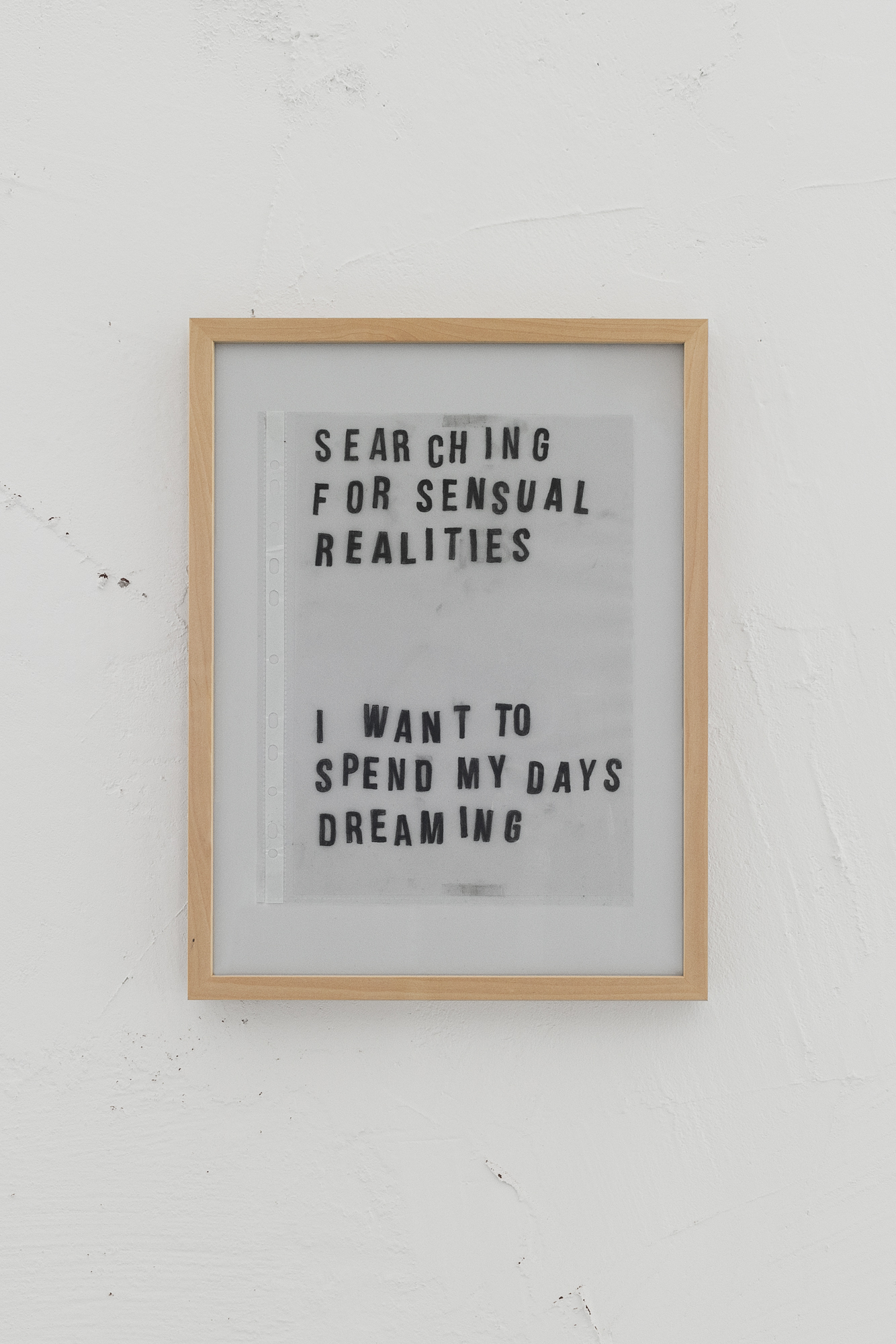

Sensory and visual impressions of traces, lines and contours, were the starting points for this exhibition. The experience of the imprint, the direct touch and work with or the accidental encounters with materials inspired the concept that developed in the course of its making. I was interested in the relationships of people to materials and to their (living) environment and the expressions of closeness that are found in the confrontation. The idea arose in a time, when there were no spaces nor encounters with other beings, and you were forced to engage with your material surroundings and empty space in a different manner. Topics that related to the concept were the absence of the living, longing for touch, traces of the human in the outside space, new relationships to one's material environment, new forms of (body) perception, being alone with oneself, dealing with one’s own subjective point of view...

Over time, the meaning and focus of the exhibition changed. The project counteracted the lack of discursive exchange, lack of new experiences, new social contacts and frameworks to produce work. The space in Wuppertal became a symbolic free space, one of the few spaces that one could enter outside one's own home and in which one could work, imagine and test and materialise one's ideas. The space became central. In a similar way in which Joe Defoe’s Rose Painting merged into her home by blocking her window to the outside world and thus enclosing her inside her studio/home, how it gradually with every new layer of paint grew inside her space and further reduced her ability to move in it, the artworks in Wuppertal responded to the exhibition space.

The works created for the physical exhibition opened up new spaces, virtual spaces, represent spaces within spaces, connect exterior and interior spaces, became part of the space or deal with the history of it. For example, Günther Möbius and Yvo Cho found out that iron yarn was produced in the cloth factory, and its strong durability was important for the development of some iconic Bauhaus chairs. These chairs, which were intended to make arts and crafts accessible to the masses, now represent luxury items that in the cultural sphere are reserved for only people in leading positions. By reappropriating these chairs and placing them in the exhibition space as an invitation for visitors to take a seat, they merge with the exhibition architecture, refer to the history of the space and its relation to the present, and mark the space as non-hierarchical and interactive.

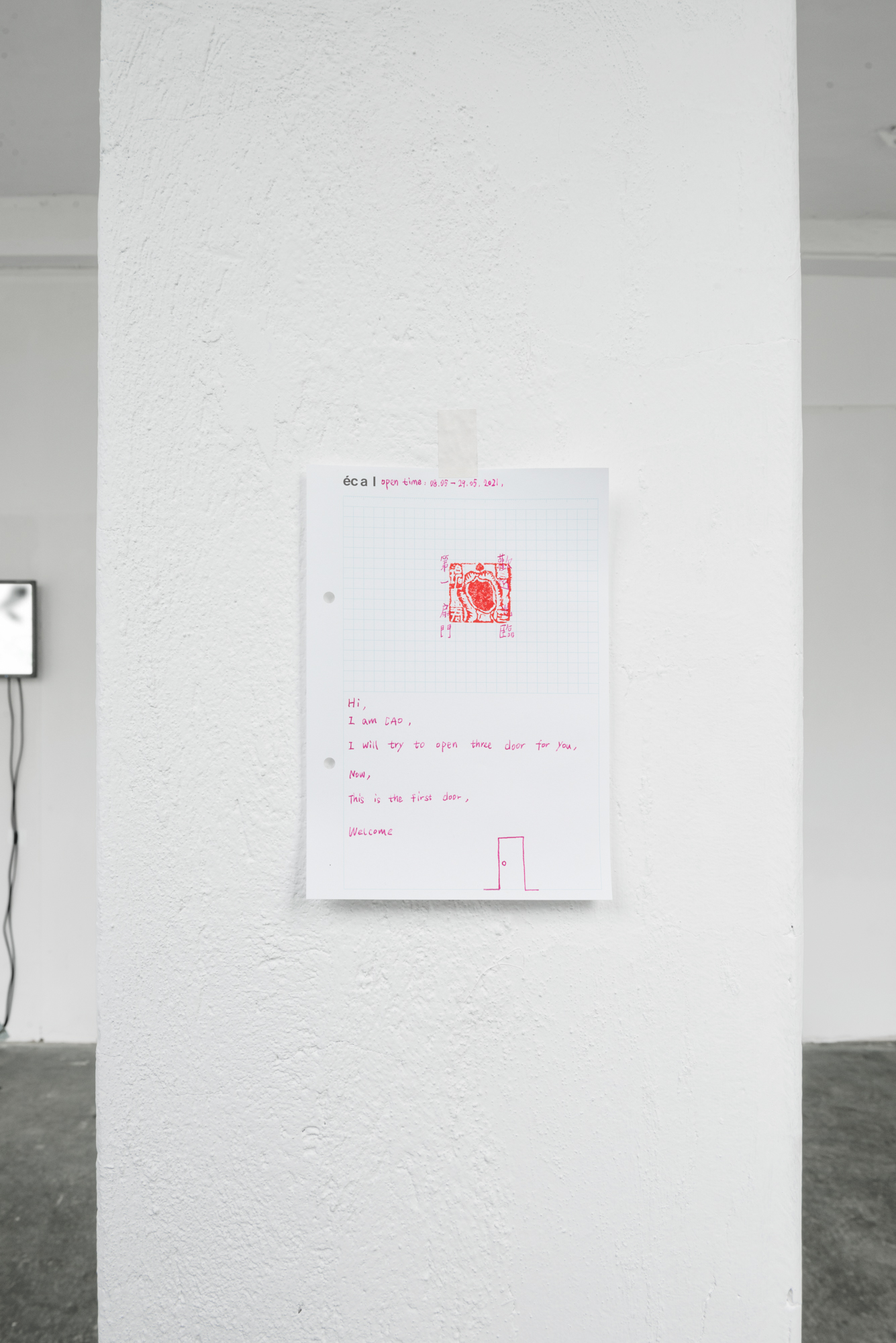

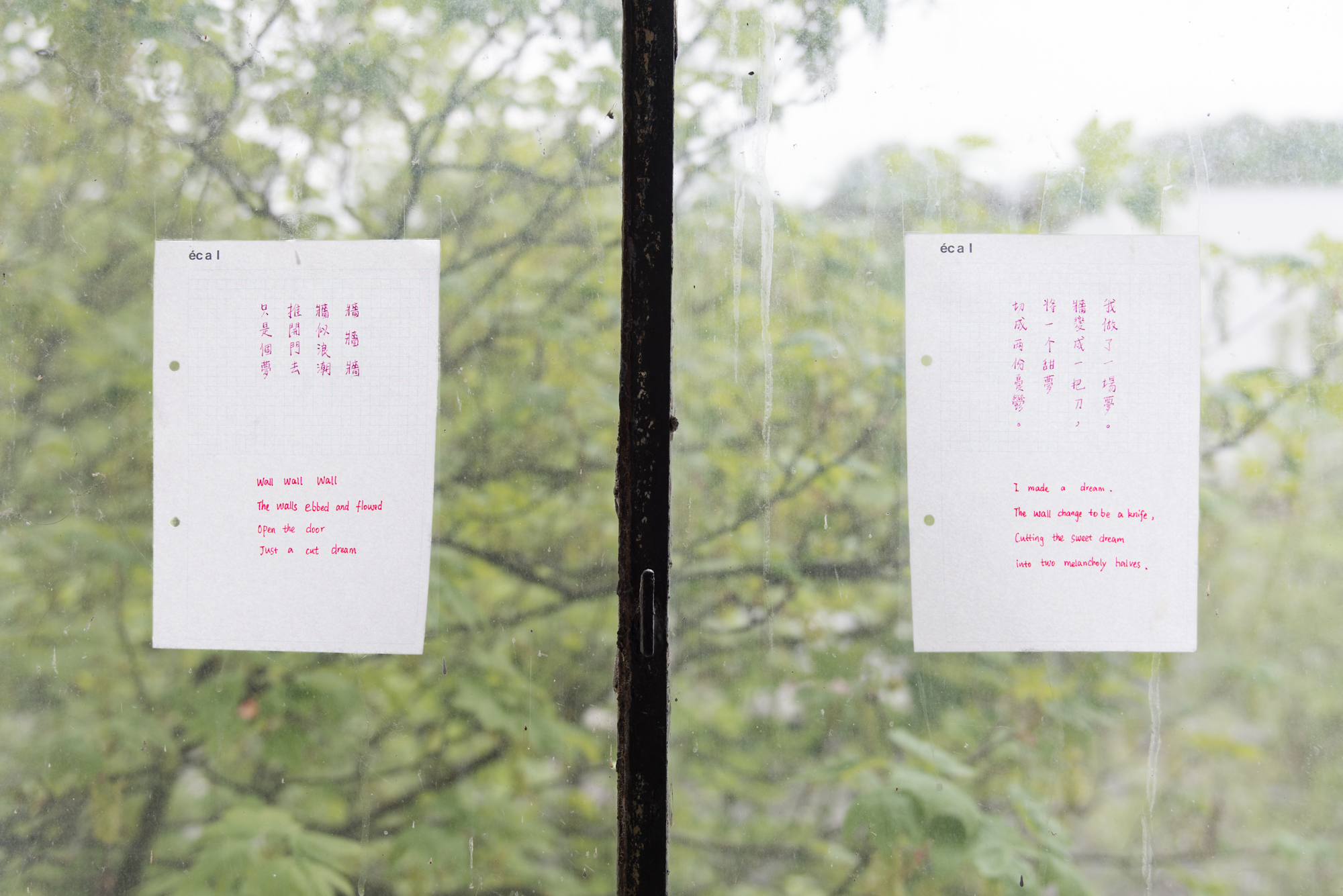

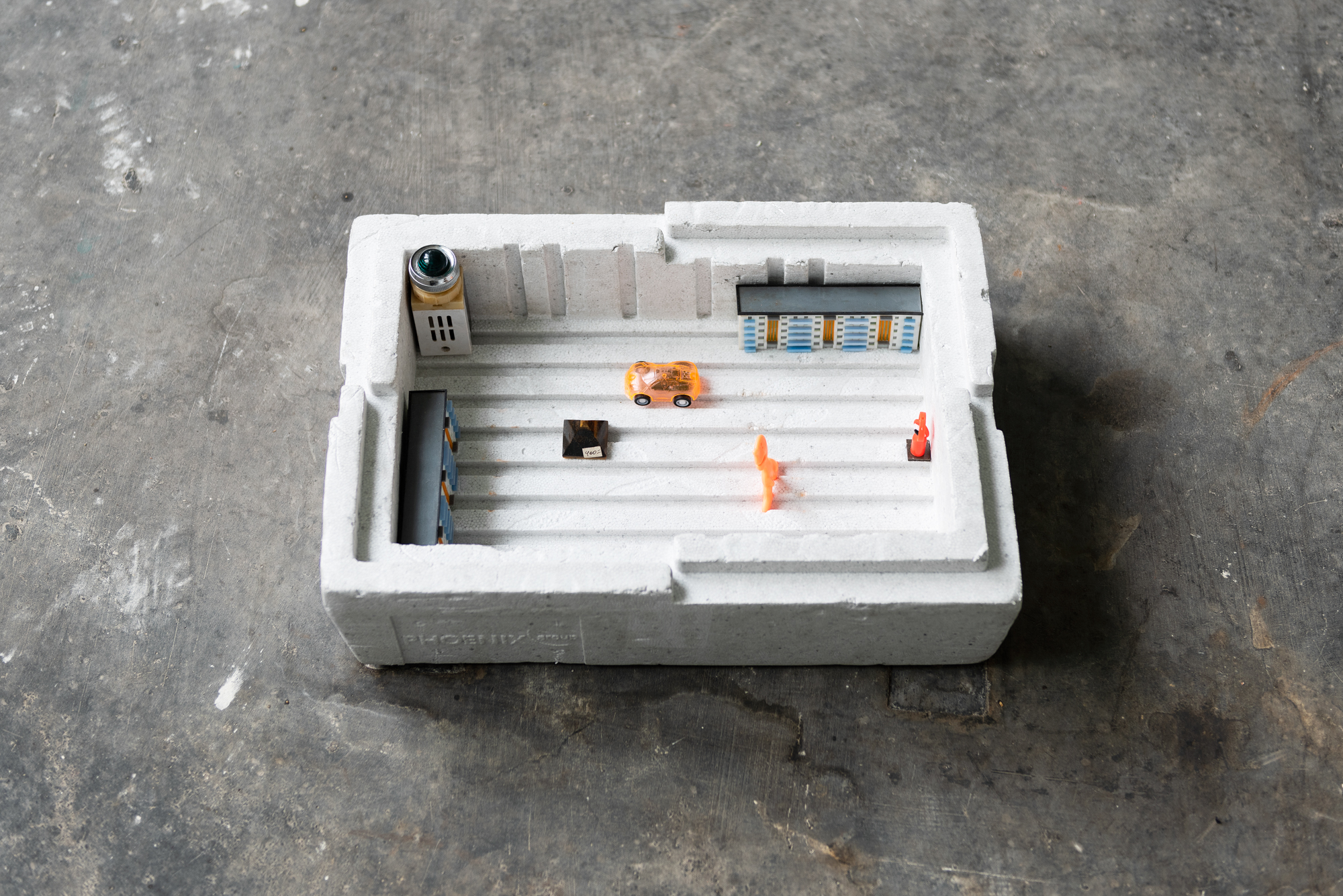

Cao Bijun presented the first part of her new exhibition series, in which she creates spaces within spaces and "opens doors". Visitors were invited to interact with photographs and objects she scattered across a space and leave their contact details to be led into a new room at the next opportunity.

For their work "Alosa Alosa!", the Berlin-based collective_tentativ.lu combined a series of photographs and objects. „Or How to Pitch a Tent!", she combined various found textiles, which she processed with prints and paint. The result is an amorphous, moving, kinetic sculpture reminiscent of a tent. Kollektiv_tentativ.lu run a project space in a former bread factory in Brandenburg, and through their work carried their space into the new one. Tim Dönges deals with symbols and signs in pop culture and street art and adopts minimalist gestures of graffiti for his new work. The mirroring, modular painting he made for the space combines with the colourfulness of the surroundings and picks up on the window front and the pattern created on the floor when light passes through it.

From the same wall, stand out the two swans by Thomas Lambertz, who freezes a moment of battle between rival swans in the sculptural work. Their long necks can become entangled in the quarrel, from which they cannot free themselves. From the initial repulsion, a tragic and involuntary closeness emerges.

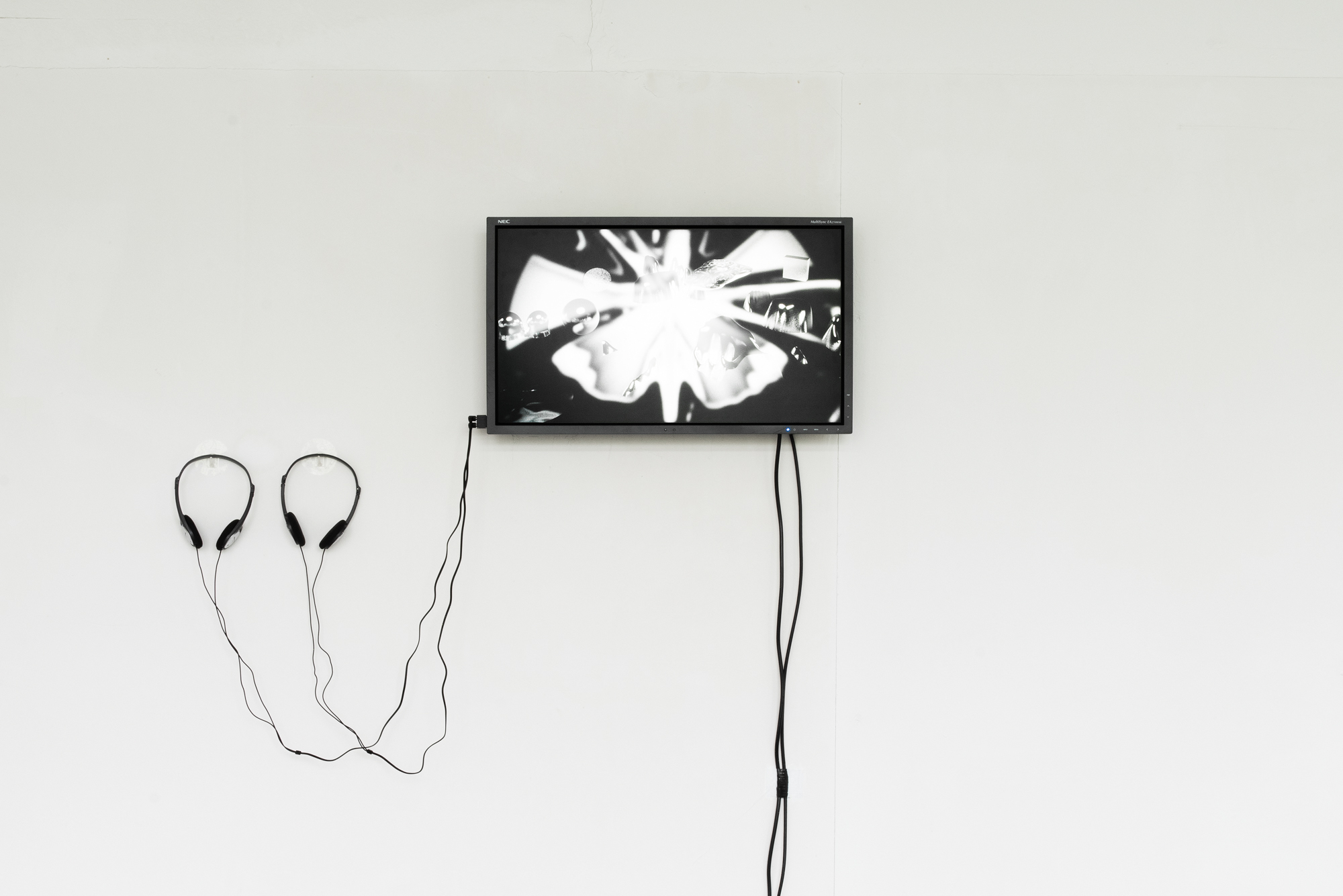

Li-An Hong works with 3D animation and created a film in which the physical properties of spaces were depicted in an abstract way. Jeesoo Hong filled the gaps of the space with her sound installation "51°16'07.1 "N 7°14'05.6 "E". She attached a contact loudspeaker to a pane of glass in the room, which amplified the sound of the Wupper River flowing past the building at the bottom of the exhibition space and carried it into the exhibition space.

Hidden behind a PVC curtain with integrated photos in one corner of the room is a video installation by Dagmar Buchenthal that explores ways of looking at the female body. Felix Miebach's photograms, on the other hand, question the everyday and its symbols, summarising the investigations in a diagram similar to a star chart on photosensitive paper.

From the small, often domestic environments, the works were carried into a large space for individual discussions of the works and, finally, a finissage at the end of May. From observations of changes in the outside space, the work moves into the observation of the inside space and the struggle for free spaces.

The endurance and focus Jay DeFeo needed to work on „The Rose” still permeates through the painting to today. It is a concentration that emerged from the synthesis of her body, her environment and the canvas. From one line, from several lines, from a hand movement, something emerged that became one with the space. A trace is followed and then the work melds into the background and the space moves into the foreground. The presence of the artists step behind the works or into the works. Digging up the story of the buried work of art for us meant excavating a lost method of creating a work which is concentration and focus upon its own materiality.

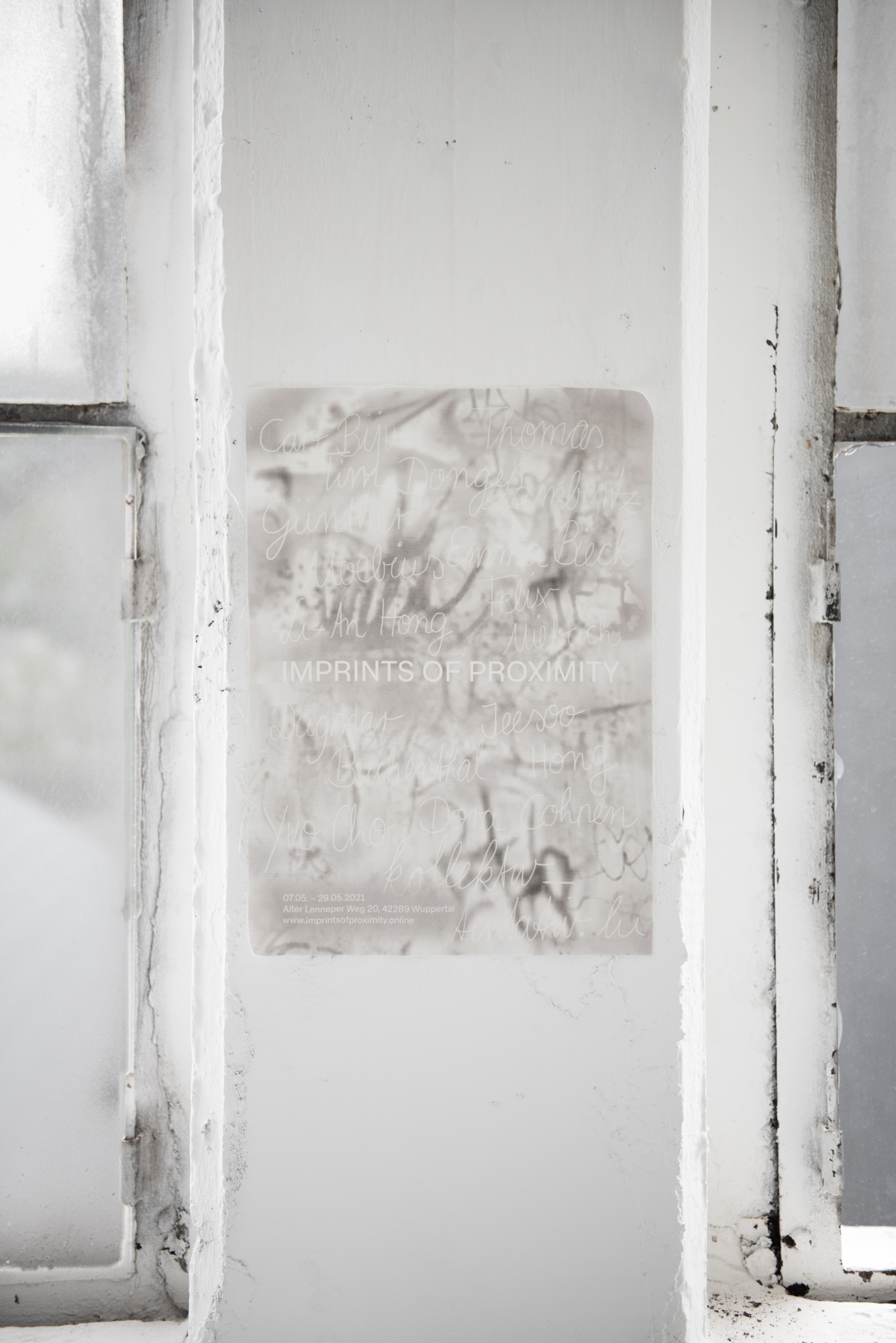

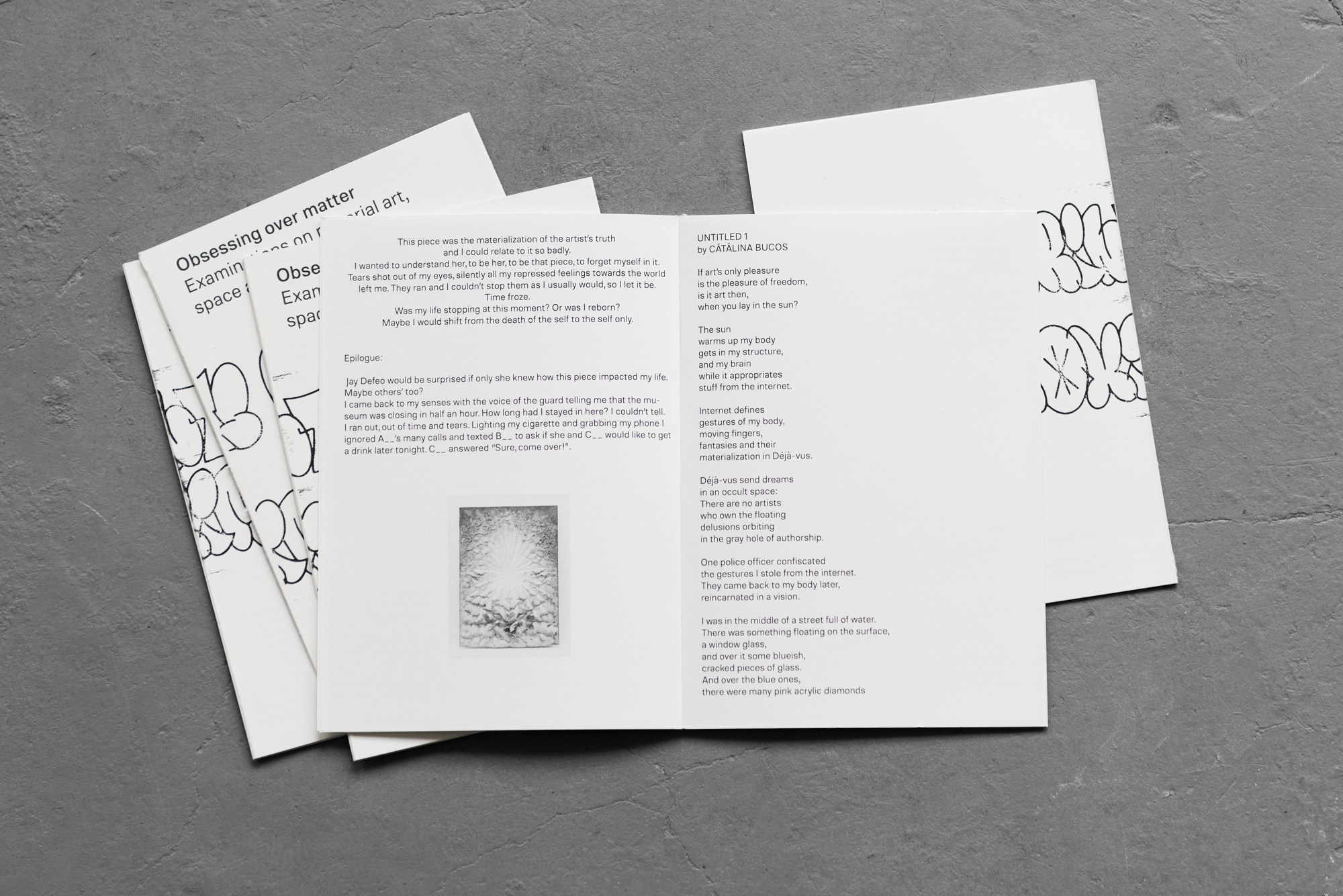

Salima Moisserons short story on „The Rose” by Jay DeFeo was printed in the reader that was published alongside the exhibition. The authors of the publication deal with aspects that were inspired by the artworks and the concept of the exhibition. While Theresa Widua negotiates the differences and similarities between physical and immaterial spaces in her text "(Im)material Bodies in Virtual Space", Catalina Bucos writes about the artist's body, which moves between reality and dream and the internet. For the magazine in which the texts were collected, Ruben Cohnen developed the typeface, and Finn Brauckmann created illustrations.

You can have a look inside the reader: here.

Emma Bieck & Dora Cohnen